Professor C. continues his seminar series, in this case with Henry James,and “The Wings of the Dove.” Reading back through all my father’s posts here, (click on “(Professor C. in the Topics sidebar) I think I find threads about language, reading now vs. then, and the changing choices for identity as society has loosened over the last 100 years. But I could be wrong. That’s the good part about words, flexible interpretation. Oh, by the way, in this movie Venice beats the clothes – hands down.

Reading late Henry James is difficult, sometimes exasperating, sometimes exhilarating. I plead guilty – well, partly — to his charge: “the faculty of attention has utterly vanished from the Anglo-Saxon mind, extinguished at its source by the big bayadère of journalism, of the newspaper and the picture magazine which keeps screaming, ‘Look at me.’ Illustrations, loud simplifications… bill poster advertising – only these stand a chance.” If James thought the faculty of attention had diminished in his day, one hesitates to imagine what he would think of our 140 character tweets and twittering. Some of James’s paragraphs go on for 1,000 words.

For those who haven’t attempted the late James, I’ve chosen a few difficult lines as a sample from a long paragraph in The Wings of the Dove, the story of a complicated triangle involving the Englishwoman Kate Croy, who lives with her aunt because her mother is dead and her ne’er-do-well father is penniless; the very rich American Milly Theale, dying of a mysterious illness; and the English journalist Merton Densher, betrothed to Kate. Because her aunt disapproves of Densher, Kate and he meet clandestinely in a museum – not, as they have before, in Kensington Gardens, because that “would have had too much of the taste of their old frustrations.” The museum “had been a variation; yet Densher had at the end of a quarter of an hour fully known what to conclude from it.”

What follows is a hyper-Jamesian struggle to occupy the minds of his protagonists: “She might be as nobly charming as she liked and he had seen nothing to touch her in the States” (where Densher has met Milly Theale on a visit); “she couldn’t pretend that in such conditions as those she herself believed it enough for him. She couldn’t pretend she believed he would believe it enough for herself. It was not enough for herself—she showed him it was not.” Things go on in this obscure vein until, at paragraph’s end, the triangular plot of Densher, Kate, and Milly assumes a sudden, more visible shape; they “stumble upon” Milly, “his little New York friend,” and Densher pauses over the surprise of “little”; “He thought of her for some reason as little, though she was of about Kate’s height, to which, any more than to any other felicity in his mistress, he had never applied the diminutive.” We are several hundred pages into the book. Coming across these lines, the reader begins to understand, as with a jolt, the trajectory of the story. James’s late fiction depends on an ever so gradual of lifting the veil of meaning that obscures the mysteries of human behavior.

It all ends sadly. Milly, knowing that she is dying and wanting to “live all she can,” James’s great theme, proposes a trip to Venice. Kate, her aunt, and Milly’s traveling companion Mrs. Stringham set forth. Densher follows, and things play out in the lush surroundings of La Serenissima. Kate wants Densher to marry Milly and then, when Milly dies, inherit her money. Densher agrees only on condition that Kate sleep with him. Hearing of their scheme from Lord Mark, whom Kate’s aunt has hoped she would marry, Milly “turns her face to the wall” — a turn of phrase echoing a Victorian music hall song (“Turn ‘Erbert’s Face to the Wall, Mother”) but exquisitely pointed here. Milly turns toward the wall in her “real” life; it’s her portrait that James the master turns to the wall, removing her from our view. Densher, back in London, hears of Milly’s death and learns that, despite knowing of the plot against her, she has left him a large sum. He tells Kate he won’t marry her unless she agrees, with him, to turn the money down. If she refuses, he offers to make it over to her.

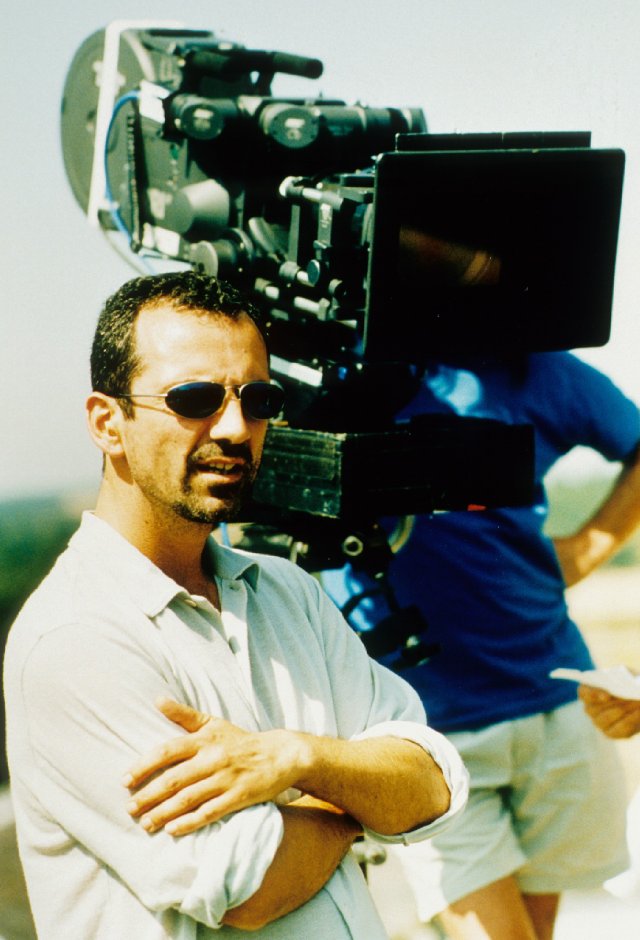

The 1997 film, directed by Iain Softley, script by Hossein Amini, with Helena Bonham Carter as Kate, Alison Elliott as Milly, and Linus Roache as Merton Densher, is a one-off triumph, not James exactly but James as he might have been, had he been reborn as a screen writer in 1997. The film is set in 1910, eight years after the novel’s publication in 1902. Anything that happens in 1910, in historical retrospect, has the anticipatory look of catastrophes to come. The first great war is four years away. Historical memory endows 1910 with an aura of foreboding.

This later setting of the film is purposeful. The date also hints at modernity; Queen Victoria died in 1901. When the ailing Milly visits Sir Luke Strett, “Consultant in Radiology” (suggesting to the twenty-first-century mind that Milly’s illness is cancer, as is never specified in the book), we may wonder if radiology had become a full-fledged medical specialty by 1910 – but 1902 would be much more of a stretch. If the year is 1910. perhaps we’re also less shocked at so un-Jamesian a scene as that of still virginal Kate and virginal Milly finding themselves at a bookstore in a section “only for men,” opening a book to the image of a grotesque, comic, sexual tripling — and giggling hysterically. If we’re not shocked, however, we may wonder for a moment if the scene is gratuitous. I think it is not. The novel is about money, love (and sex). The film is about money, love and sex equally.

Flash forward toward the end. Milly is dead, Kate and Merton are in London. He has been home for a fortnight but has not been to see Kate. She knocks on his door, he hesitates but finally lets her in. He hands her a letter from Milly, unopened but, they both know, telling him that she has left him money. She drops the letter in the gas fire, then goes into the bedroom, undresses and lies on the bed in a fetal position. Densher comes in, sits on the bed, she embraces him, takes off his sweater and clothes. They make love, Milly astride, the camera watching her full face, deeply in pain. The line between sex as the release of pleasure and that of pain, in this case the pain of an ending and of things gone horribly wrong, could not be more vivid: Kate’s face is a study in anguish. And, as in the comic pornography at the beginning, three people are involved; but this is no comedy and one of the three is dead, at rest in San Michele, Venice’s cemetery island. The funeral scene is not depicted in the novel – the emotion lies too close to the surface for James’s comfort — but the camera work in the film, sumptuous yet reticent, succeeds beautifully.

The film’s ending also veers away from the novel, though in each Kate makes it a condition of marriage that Merton give her his word of honor that he is not in love with Milly’s memory. In the novel, when he does not answer, Kate answers for him: “ ‘Her memory’s your love.’ ” Densher says: “ ‘I’ll marry you in an hour.’” “ ‘As we were?’”, Kate asks. Densher: “ ‘As we were.’” But Kate turns away, as Milly has turned away in dying: “ ‘We shall never be again as we were.’ ” In the film, when Kate asks for Merton’s word of honor, he doesn’t answer, the scene fades out, and we are suddenly back in Venice. Remembering Milly’s telling him that she has a “good feeling… everything’s going to happen for you soon,” Merton steps out of a gondola with two suitcases, turns a corner and is gone from sight. Milly’s good feeling was that Merton and Kate would have her money, ironic then because it could be fulfilled only on her death, ironic now because Merton has refused the money. But not merely ironic because, as he turns the corner, Merton is on his way to some possible future. In the novel, Kate and he are locked forever in the embrace of an uncertain ending. The Venetian light offers more comfort than the airless interior of the novel’s last words.

I called the film a one-off triumph. Why one-off? Helena Bonham Carter is a considerable star, as is the wonderful Michael Gambon, who plays Kate’s opium-addicted father. But the film stands out uniquely in the work of Iain Softley and Hossein Amini, the director and the screenwriter, as it does for Linus Roache and the little-known Alison Elliott. As Milly, Elliott is beyond praise. The wistful smiles that light up her freckled face (you see the freckles in a close-up), knowing all the while that the end is not far off, are a counterpoint to Kate’s troubled countenance. Kate never smiles; the contrast is as well acted as it is skilfully imagined.

The movie isn’t perfect, nothing is: the rain that falls again and again is middling symbolism and – as a New York Times reviewer noticed – it looks phony; sometimes you can see shadows as the rain pours down. But “The Wings of the Dove,” if not perfect, comes pretty close.

15 Responses

Prof C does have some interesting insights especially regarding setting the movie in 1910 and while I haven’t yet read this James novel the passages he cites and interprets are quite interesting and ring true with what I do know. Every time I hear “late James” it’s usually with a wincing shrug. I usually run from modern literary scholarship as it always seems so intent on chasing away the beauty.

Lisa, your last statement is one of the reasons why this movie works so well. These days the clothes often co-star and intrusively overpower characters and narrative with an eye towards a Vogue/Vanity Fair photo spread or a Tiffany/Golden Bowl collaboration. This movie was perfectly cast and that includes having the wardrobe mistress know her place. My only quibble was the last scene-I was beginning to think they brought Eve Ensler in for a rewrite. The scene (and movie) was so well acted I didn’t need HBC sticking her nether regions in my face to help me with the “raw emotion”. I concur with Prof C’s “near perfect” pronouncement and I’ll netflick it again with his keen insights in mind.

I’m not even going to pretend I’d slog through the book – my preferences are for something in-between a 140 character tweet and a 1,000 work paragraph. This enticing review this has pushed the movie up my queue, just as soon as I finish Season 2 of “Justified.”

I never minded James’ complex prose. It has the effect of slowing down the reader, creating a mood in which the story can be better enjoyed and appreciated.

Fascinating post. I’ve never read anything by Henry James, except for “the Turn of the Screw” which my Dad recommended to me when I was 13. I don’t remember it at all, except that I thought it was spooky, and thus cool. Which of James’ books would Professor C – or you – recommend for a second foray into his work? Would it be “Wings of the Dove”?

Hello, Murphy —

Try Portrait of a Lady (it’s early James).

Prof. C.

Clearly I should get back to some serious reading, though perhaps James is a bit of a stretch with a 10 month old.

This essay was lovely, and the movie I remember as being wonderful. I slogged two hours into LA to see it at 17 (partially because of the production design, I’ll admit). I should probably watch it again, having now been to Venice.

Thanks for the recommendation, Prof. C!

I like to read classic literature and all the greats on PBS, BBC, and the like. I recently watched this movie on Netflix and liked it fine. But the whole time I watching I felt like something was left out, like I was missing something. So I thought I might get the book and see what I was missing, but it was late, the library was closed, and I was in my PJs (not my yummy sushi pajamas). I looked it up on Wikipedia and realized I didn’t really want to read the book. Wikipedia filled in the gaps ans I was quite happy with the movie, though I would have like more scenes with the aunt because I quite like that actress.

Well, this post certainly brought out everyone’s testosterone didn’t it:).

I usually monitor comments super tightly but in this case I’m going to leave all this up, and assume it was friendly banter. If not, and if anyone wants me to edit at all, send me an email and I will get out my red pen.

I do hope there is no need for the red pen and thank you again for a great post and bringing Prof C’s archived selections to my attention. I’m a huge Wharton fan.

No red pen requests. Phew. GSL, thanks for reading and commenting. Having Professor C. post here, now retired from Stanford but for decades a tenured professor in the English department, bumps up my intellectual cred to no end:).

I loved the film and enjoyed this post. I enjoy all of Professor C’s posts. As for the book, I probably won’t read it. I think I’ve read all of the James novels I want to read.

You know our exchange here was quite tame compared to that House of Mirth dustup (Prof C opened with) that got really nasty. I think the idea of comparing those literary films/novels is a fabulous idea as it doesn’t require a major time investment if you just want to do the movie and is interesting even if you haven’t done either. Looking forward to the next one and btw it’s the bicentennial of Pride & Prejudice…?

Congrats on the marriage and retirement!

I spoke too soon, red pen request received and executed. Carry on.

The settings cannot be underestimated, especially the early scene in Lord Leightons house where the characters shimmers against turquoise Persian tiles.