Class convenes. Professor C. comes at last to Henry James. A natural fit, no? To all the new readers, welcome. Professor C. is my papa.

Why didn’t Henry James include Washington Square in the great New York Edition of his works (1907-09), a massive project of choosing, commenting and revising that he looked on as his ticket to posterity only to be disappointed by a tepid public reception? Even Jamesians more inclined to the dense intricacy of the late novels would agree that Washington Square – the story of a very shy, very plain heiress, Catherine Sloper; of her cruel and viciously attentive father, Dr. Austin Sloper, always comparing Catherine unfavorably to her late mother; and a handsome, suspicious suitor, Morris Townsend — is a short masterpiece. Why then not include it? But James discovered he couldn’t even reread it. “I can’t” he said.

Jamesian questions are freighted. Maybe no American writer takes up more space on library shelves. Commentaries, biographies, criticism lie thick on the ground. I have read only the smallest part. But I think the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Washington Square has an answer to the problem of the novel and its exclusion from the New York Edition. Having offered structural reasons why the novel might have resisted revision, Adrian Poole then tiptoes up to another kind of reading: “There are of course other possible reasons tied up with James’s personal involvement in the past in which the novel is set: some of the raw matter lurking beneath the surface might have been simply too painful.” Just, I suspect, so.

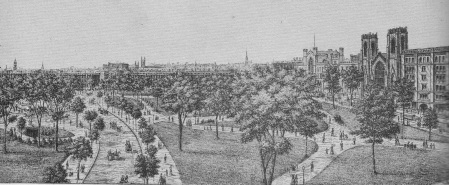

Washington Square is a painful read. Pick up the narrative anywhere, and you are caught in a society where everything is under scrutiny all the time, everyone is watching everyone else, every introduction (Catherine is embarrassed by introductions), every farewell, every gesture, every word is accountable. And, at the center, Miss Sloper, “shy, uncomfortably, painfully shy,” suffers most. Here is what the claustrophobic world of Washington Square is like. It is a family evening at Dr. Sloper’s sister’s. He leaves the room briefly and, coming back, sees Catherine seated on a small couch next to the newly-arrived Morris Townsend. A distinguished medical man, proud of his diagnostic skills, Dr. Sloper “saw in a moment, however, that his daughter was painfully conscious of his own observation. She sat motionless, with her eyes bent down, staring at her open fan, deeply flushed, shrinking together as if to minimize the indiscretion of which she confessed herself guilty.”

Of course it is Morris who has “lost as little time as possible in seating himself on a small sofa, beside Catherine.” That does not excuse her in her own eyes or those, she imagines, of her father. On the Web I find an article called “The role of shame, guilt and embarrassment in online social dilemmas.” No need to read it: Henry James got there first, just not online.

James goes against the American grain. When I was in graduate school (long ago) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, American literature was the province of three bull elephants on the English faculty who saw themselves as being, first of all, not “old Europe” (in the words of Donald Rumsfeld, Princeton,1954). One exceptional Americanist, much different in temperament and a student of James, had died before I arrived. As a result, “American Studies” seemed to me a religion of toughness; or pseudo-toughness. American “exceptionalism,” that fetish of the contemporary right (and not just the right), reflects even at this distance a cultural mythology. The heroes of American Studies were the likes of Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards, James Fenimore Cooper, Hawthorne, Melville, Whitman, Dreiser, Hemingway. Women were admitted only through the back door of “regional literature”: Willa Cather or Sarah Orne Jewett.

James did not fit the model. So it happened that I read him for the first time in a summer class, taught not by one of the local faculty but by a visitor from Columbia, the civilized, eclectic, humane Fred Dupee. After his death, Mary McCarthy wrote a tribute: “ ‘He’s French, you see,’ Edmund Wilson used to emphasize in his roaring voice.” In fact Dupee came from the middle west, but his sensibility did not resemble those of the elephants. “Fred wrecked many pretentious and ill-considered schemes in the department” – these the words of a younger colleague at Columbia – “just by sighing at the right time in a meeting.” He was the right interpreter of James. Early in that summer I read Washington Square. What I remember is a feeling of menace, a sense that this was all more than I could handle. I think I understand now what that feeling was about.

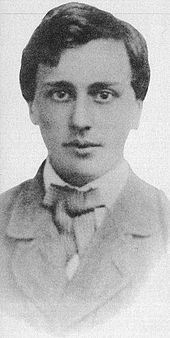

Early in the novel is a deeply strange passage in which Henry James the narrator addresses Henry James himself who was born in 1840, the very moment of the novel’s setting, in his grandmother’s house at 21 Washington Place, off the Square:

“It was here that your grandmother lived in venerable solitude, and dispensed a hospitality which commended itself alike to the infant imagination and the infant palate; it was here that you took your first walks abroad, following the nursery-maid with unequal step and sniffing up the strange odour of the ailantus-trees which at that time formed the principal umbrage of the Square, and diffused an aroma that you were not yet critical enough to dislike as it deserved; it was here, finally, that your first school, kept by a broad-bosomed, broad-based old lady with a ferule, who was always having tea in a blue cup, with a saucer that didn’t match, enlarged the circle both of your observations and your sensations. It was here, at any rate, that my heroine spent many years of her life; which is my excuse for this topographical parenthesis.”

Here is raw and painful matter beneath the surface: disingenuously, James calls his digression “topographical” but it is hardly that. Has a novelist ever cast his lot so nakedly, so painfully, so personally, with his “heroine?” Years later, in the first volume of his autobiography, A Small Boy and Others (the title reveals a lot), James compares himself and his formidably talented older brother William: “what comes to me is that I … hung inveterately and woefully back.” Hanging “inveterately and woefully” back could be a description of poor, shy Catherine Sloper. That is why I think Adrian Poole may be right: that Washington Square is not in the New York Edition because the story cut so close to the bone.

Catherine’s story ends sadly, as you would expect. Her father takes her to Europe, the customary treatment to discourage daughters from undesirable suitors or to conceal out-of-wedlock pregnancies. It doesn’t work, but Morris Townsend bows out, knowing that Dr. Sloper will disinherit Catherine if she marries him. Years later he returns, a widower, his good looks mostly gone but hoping to renew his attentions. Catherine, who has refused to promise her father she won’t marry Morris after Dr. Sloper’s death, nonetheless turns Morris down. The last we see of her, after this final visit, she has returned to her needlework, seating herself with it – “for life, as it were.” “As it were,” the very last, very Jamesian word. Even so, in Catherine’s steadfast spinsterhood (she has turned down a suitor or two), she emerges from the ordeal stronger than anyone else, her father included. As James himself would do, she sticks to her needlework.

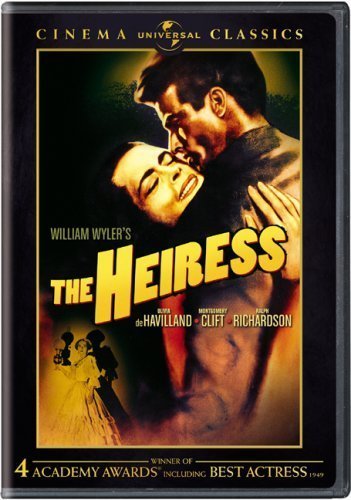

Washington Square was turned into a play, “The Heiress,” and the play was turned into a film (1949) by William Wyler, with Olivia de Havilland, Errol Flynn’s frequent on screen partner, submerging her own beauty as Catherine; Montgomery Clift as Morris Townsend; and Ralph Richardson as Dr. Sloper. De Havilland won the Academy Award; Richardson was nominated for best supporting actor and surely should have won for his chilling performance (who remembers Dean Jagger in “Twelve O’Clock High”?); and the film was a big success. Adapting James takes very good acting indeed. How to translate (for example) the dark, obscure cruelty of Catherine’s father: “”you would have had to know him well to discover that on the whole he rather enjoyed having to be so disagreeable” So much of the James manner depends on adverbial qualifiers: “on the whole he rather enjoyed having to be so disagreeable.” It seems untranslatable, but watching the film, then looking back to James’s text, you recognize the perfection of Richardson’s performance.

Small touches enhance the story. In the novel, Morris tells Catherine, “I sing a little myself … some day I will show you. Not to-day, but some other time.” In the film (as I imagine in the play), he plays and sings “Plaisir d’Amour.” I wondered if that was an anachronism, but no, “Plaisir d’Amour was composed in 1790. Its foreboding theme, that love’s pleasures are for a moment, its sorrows for a lifetime, matches the events to come. The musical score alludes to the tune from the start, sometimes heavy-handedly (it’s said William Wyler thought Aaron Copland’s allusions in the original score were too sophisticated for a film-going audience), but for the musically unsophisticated (myself), often oblivious to film scores, it captures the ear.

The film (and I’ve been told, the play) takes big liberties with James’s ending, but if the result is a different story from the original, it doesn’t seem entirely out of line. Morris Townsend has not to our knowledge been married when he returns; he is not “fat and bald,” as Dr. Sloper describes him in the novel; Catherine has had no suitors in the intervening years; and she has grown vengeful. She encourages Morris to think she will marry him but bolts the door when he comes to claim her. The dish of revenge has seldom been served more cold. Having just finished the final stitch of the final letter “Z” on her fancy-work, she goes up the stairs of her house as Morris pounds at the door desperately. The film substitutes a noisy ending for a quiet one, melodrama for resignation. Myself, I wish Wyler had reverted to the original quiet ending, as Scorsese did in “The Age of Innocence.” But after all that Catherine has been through, it’s hard to begrudge her recompense.

Images

Washington Square, via Penguin Classics, Henry James’ study via Mantex, Washington Square in the 1880’s via Ephemeral New York, James at 16 via Answers.com, The Heiress poster via IMDb, Ralph Richardson via actoroscar, Oliva de Havilland via The Ticket Booth.

30 Responses

A beautifully written and informative post. Will read it again later when I’m more awake. I have read the novella, seen the film, and saw a theatrical production in Los Angeles, with Cherry Jones as Catherine. All 3 experiences were fantastic, different, but equally affecting. I actually cried (along with some others in the audience) at the end of the play. Just got goosebumps writing this. Yes, so painful. More later and so happy to have you back!

I thoroughly enjoyed this analysis. Thank you very much!

Ah, how I miss my literature classes! I was focused on Euro-centric reads while in college so I missed out on reading and discussing American authors. Thank you for the insights on James. I’ve not read anything by him but I did see the film version. I thoroughly enjoyed it even though it broke my heart to watch a woman waste her life while upholding her society’s narrow expectations of her.

I just bought a Kindle and have been pondering what to stock in my virtual library. James is a good start!

You’ve made this English major’s heart race. Thank you for this post.

Thank you for this wonderful review, I can’t wait to read the book and see the film!

As an aside, you might enjoy this wonderful blog featuring selections from the correspondence of William and Henry James:

http://williamandhenryjames.blogspot.com/

i wrote what i thought was a terribly incisive analysis of washington square for george dekker late one night at la maison française; when i read it en route to class a few hours later, it still seemed serviceable. i didn’t realize until i regained the essay a week later that, despite having read the novel, i had – alas! – managed to refer to that all-important square as “washington park” throughout. as they say, cram doesn’t pay.

Utterly fascinating. I loved “The Turn of the Screw” but for some reason I have never read much Henry James beyond that. Washington Park sounds painful but brilliant.

Washington *Square*, not Washington Park. Oh dear.

At Lisa’s suggestion, I immediately ordered both the book and the movie. Reading this post, I am now even more excited and can’t wait to curl up….

Wonderful post. Such a treat to read sitting here at the computer during my lunch break at work. I miss my English lit classes, too. As an aside, Lauren, I once submitted what must have been a tortuous essay with “Shakespear” rather than “Shakespeare” throughout. There was a red cursive “e” after every spelling. Ouch.

This was wonderful, think I have a new book to add to my reading list!

Honestly, nothing since 1999 has made me want to go back to Literature classes as much this informal series with Professor C.

Thank you for your insightful discussion. Your comments made me consider Henry James compared to himself and to other authors.

James often features these mean-spirited, controlling characters such as Dr. Sloper or Juliana Bordereau (The Aspern Papers), who create a poisoned atmosphere in which people are stymied from moving in any direction—a symbolic death as for Catherine Sloper, or a real death as for Daisy Miller.

Other tragic stories don’t always have the same complex psychological relationships. Dreiser’s “heroes” suffer as a result of their own bad decisions and unsuccessful navigations through society, while the outright abusive Mr. Barrett in Besier’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street frightens the reader as much as he does the characters, in spite of a few weak attempts to pass him off as simply an irascible curmudgeon.

You point out the autobiographical aspects of Washington Square; perhaps James is warning us not to get ensnared in the psychodramas (mishegoss) of others, which like Greek curses, are easily passed from generation to generation.

–Road to Parnassus

Being an old English major, I wish I could read an essay like this every day. Absolutely gave a delicious dimension I have been missing for many years. Thank you enormously.

“Being an old English major, I wish I could read an essay like this every day. Absolutely gave a delicious dimension I have been missing for many years. Thank you enormously.”

MMM, you put that so well, I’m just going to piggyback on your remarks if you don’t mind. Closer to the truth is I’m speechless. What an exquisite bit of writing, thinking, positioning, running with then doubling back, framing, all the while revealing just enough about himself to stay in possession of it, who else do we know like this? My desklight is such that I often glimpse my face as I read, sometimes I know the woman I see in the reflection, today I did not. Hm.

Parlor game: composing guest list for my dream dinner table for 10. Adding Prof C and Lisa C. Hope you can come. Let’s dress, shall we?

The analytical, emotional melting pot. Interesting perspective. I’m certain this book is here somewhere, “… hung inveterately and woefully back” on my shelves.

Class dunce chiming in to say I am behind on this assignment but really, truly look forward to finishing the book (which I am loving so far), watching The Heiress and then returning to this post which is filled with the level of insight we just never seem to achieve during the Thursday night book group. Thank you so much for this, Professor C.

Thanks very much, everybody; it’s all been a good chance for me to catch up on filmcraft — something I’ve not understood very well in the past.

Lauren: George Dekker was an old friend, much missed. Probably he didn’t mind too much that you called it Washington Park??

Prof. C.

Dear Professor C.,although I teach literature (the French kind), this comment is not for you ! Lisa, I have just read your last three posts, and my, I love your grey hair ! So I have decided that this frog W.A.S.P. is going to stop dyeing from now on. Free at last, free at..etc. Thank you for liberating me ! Please keep inspiring …….

Wow, thanks Professor C. I am reading Claire Messud’s The Emperor’s Children for a Post-9/11 literature English class, and I find a lot of parallels between what you’ve written about James and what I’m seeing in Messud’s book. I was thinking yesterday about how all of Messud’s characters have a sort of double-consciousness (thinking of DuBois here) and it seems like the character of Catherine in Washington Square might also. I’m going to try and read the James story this weekend – it might make an interesting essay/research paper topic when compared with other novels of the post 9/11 genre.

Thank you for such an informative post on Henry James. The only book I have read of his was “The Turn of the Screw”

Some years ago we had a holiday home in Rye,East Sussex 2 houses along from Lamb House Henry James’s home.The small town was full of Americans’visiting the house and gardens each Summer.

The small bookshop stocked most of his books and did a roaring trade.

Sadly not with myself but you have whetted my appetite so will try and remedy on my Winter evening reads. Ida

Off topic (as I always was in class too) but, I never have liked Willa Cather much, and don’t understand all the hoopla. If you have some (very missed by me) appreciation for her, and would like to do a post – I’d really love to read it. It has always bothered me, that I don’t like her writing.

I really enjoyed your post. I somehow missed reading Henry James in school and instead read him after I’d been in Germany for several years and no longer needed to feel guilty about reading something in English since I ought to be practicing German. I loved everything I read despite the occasional page long sentences until I inexplicably got bogged down by The Ambassadors. One of the pleasures of my time in Germany was getting to read those big fat 19th century novels for fun. Thanks for making me feel nostalgic. I never felt that the movie versoin of Washington Square quite worked, but interesting to think about why it’s different.

Just got the book on Kindle (is it still a book? Hmm)

looking forward to the read & then will study this post.

Thank you so much for getting your dad to do this. What’s next? Would like to read it first.

Next stop.. Netflix

Lisa, so enjoy your blog.

Professor C, a wonderfully insightful analysis and review.

I will read James’ Washington Square immediately, as difficult as it may be! There will be plenty of reading time; as I am having a total left hip replacement later this month.

Karena

Art by Karena

Lisa, this story cut me to the quick a few years ago when I saw the 1997 movie version with Jennifer Jason Leigh…it was so moving, so desperately sad, and so well done that I just couldn’t ever bring myself to watch it again…or read the book! My heart breaks for women of Catherine’s ilk during the eras of Victorian & Edwardian scrutiny…what a sad life so many ended up having to endure.

Wonderful, wonderful post!!

xo J~

Thank you all. I will add only that Catherine is, in my opinion, the original Sturdy Gal. Poor at grace and gaiety, strong, able to carry her own fish, and a capacity for happiness in the right circumstances.

Interesting. I think that she’s actually Artsy Cousin if she weren’t so repressed.

I would agree with your conclusion that Henry James was self-conscious about what his stories reveal. The prefaces to his New York-edition works are almost apologetic and somewhat revisionist in that regard. His introspective intellectualism is fascinating.

I cannot believe I got to participate in this topic — no one — NO ONE around here seems to know who he was! But I do adore almost everyone I know here, so shouldn’t be such a snob…sigh~

`Valerie

A very interesting essay greatly enhanced by your own introduction to James and Washington Square. I have a foggy recollection of the Albert Finney/JJ Leigh version but it did feel Jamesian however you have really piqued my interest in the Richardson/De Havilland version and of course the novel.

Comments are closed.